|

|

BLUE SHARKS off the Red Coast By John Conner As Originally Published in Collier's, October 28, 1950 Additional Commentary by Charles Pomeroy Tokyo-At an air base in Japan, a Navy briefing officer was laying down the law to a group of pilots. "There will be no more firing at ground targets," he said grimly. "If there's to be any more shooting from now on it will be with cameras only. Or does anyone here want a court-martial?" Thus ended a strange and wonderful chapter of the Korean war-a chapter which saw big, sleek, long-range patrol bombers, intended mainly for antisubmarine work, going out every day to wage war almost in the style of fighter planes: swapping angry bullets with beached Communist patrol boats, blasting railroad trains, bombing bridges from low altitudes. For the pilots of this Navy squadron, that kind of action was a lot letter than spending long hours aloft looking for submarines that weren't there. The squadron was one of the Navy's Blue Shark outfits-flying the shark-nosed, blue-hued P2V Neptune Patrol Bomber, successor to the clumsy, night-camouflaged Catalina, which was called The Black Cat in World War II. Born to the fleet between the wars, the Neptune built up its reputation overnight in 1946 with the famed Truculent Turtle's spectacular nonstop flight from Australia to Columbus, Ohio-a performance that helped the Navy prove it had the longest-range two-engined bomber in the world. Although it is primarily a sub hunter and killer, the P2V has undertaken a wide variety of chores in Korea, watching the movement of Communist shipping, doing the spotting for warship gunnery, shepherding convoys into port and guarding the landing beaches during amphibious operations-acting, in short, as the eyes of the United Nations forces in the battle area. For this task, the Blue Shark is equipped with the latest radar equipment for peering through darkness and clouds. But in addition to its electronic eyes, the P2V packs a powerful punch:rockets, bombs or torpedoes, and both 20-millimeter and .50-caliber guns. A full salvo of its rockets is equal to nearly three times the hitting power of a destroyer broadside. The Blue Shark crews, yanked out of a scheduled six-month training stint to patrol the Korean battle area, were initially ordered to attack any worthwhile target they saw in enemy territory, in a move to step up their proficiency with that imposing array of weapons. They cheerfully obeyed.

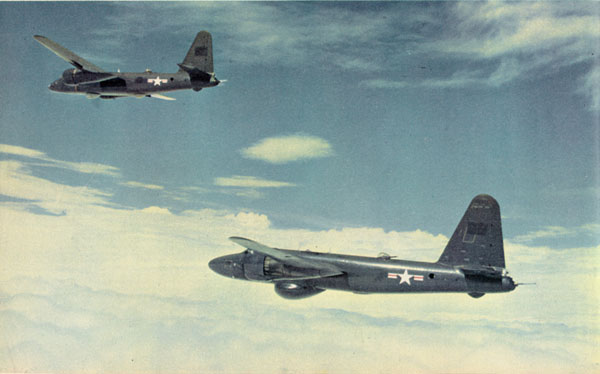

Getting ready for a mission. Lt. Comdr. R. L. Ettinger (in cap) checks engine with crew member as others file aboard Lieutenant Commander R. L. (Stretch) Ettinger, of Medford, Oregon, a six-foot five-inch giant who builds hot rods as a peacetime pastime, led the way. Ettinger hadn't fired in anger since his patrolling days of World War II and no one had yet felt the fiery bite of an attacking Shark, when one hot July day he saw a freight train steaming south out of Chongjin. He alerted Lieutenant Bill Pressler, of West Palm Beach, Florida, flying another Shark behind him, and then whipped down after the freight. Four rockets caught the string of cars dead middle and lifted two of them clear of the track in a slow, high roll. Then Ettinger called to his wingman: "Hot Rock, I want that engine. Get it for me." Hot Rock came in steeply, spitting fire and lead. The engine boiler erupted as he swept overhead. For good measure, Pressler dropped a bomb on an undamaged railroad line on his way home, leaving a twisted loop of tracks to mark his passing. As the air offensive against North Korea gained momentum, the Sharks, restricted largely to coastal patrols, tackled everything floating that had an enemy gun on it. Lieutenant Commander E. B. Rogers, of Sumner, Mississippi, squadron executive officer, got into a cove one day to check on an island that looked suspiciously like a camouflaged boat. As he approached it in a shallow dive tracers came up to meet him. "It looked as if someone was firing at me from a rock and from behind a tree," he said. "I made my run with rockets and 20-millimeters and came back for another. This time two of the 'rocks' let me have it and when I fired back eight more opened up. No matter where I turned I seemed about to get shot down. "I got two of the boats at the waterline with rockets and then got out of there-with my skin whole and six holes in the plane." The next day that same plane was shot up so badly that it had to ditch in the sea near Japan- thus ending the shooting exploits of the hard-flying Blue Sharks.  Navy ordanance men load rockets on a P2V. Hard hitting plane also totes machine guns, cannon, torpedoes and bombs. Ensign Bill Goodman of Fountain, Minnesota, and Lieutenant Commander Wylie Hunt, of San Diego-a World War II veteran who was shot down during the Battle of Midway and captured by the Japanese-were flying partners that day. Hunt, in the lead and out of Goodman's sight, made a rocket attack on a camouflaged gunboat off Chinnampo and maintained his course south toward Inchon. Goodman came on behind a few minutes later and, without knowing it had already been attacked, made a pass at the same vessel. This time the North Koreans were ready. They met him with fire coming down and going away. The top turret gunner, Chief Machinist's Mate Houston Rhodes, of San Diego, saw the tracers coming up as Goodman climbed. "Pilot from top turret-sir, we've got fire in the starboard engine." Goodman gunned his plane up to 1,000 feet, feathered the right engine and hurried out to sea to get away from the coast and capture. A P2V can fly on a single engine if it's light enough, and as this one headed home, its crew pitched everything loose out through the deck hatch. The other engine began to smoke. Rhodes, an old hand who had escaped from the sinking carrier Lexington in World War II, called the pilot again. "Mr. Goodman, we'd better think about ditching. That burning wing is going to buckle." But only when he heard that his radioman had contacted the base did the plane commander finally order: "Stand by to ditch." The plane stayed afloat ten minutes. The crew timed her from their rubber rafts and then saw her slide under in a sigh of steam. In ten minutes more Hunt was circling overhead, signaling: "The British are coming." Six hours later, just at dusk, a British cruiser and destroyer picked up the plane crew. Back at the air base the next day the bad news arrived. Admiral Joy, chief of the Navy's Far East Command, had celebrated the first loss of a Blue Shark with an angry order. It was passed on at the preflight briefing. "No more shooting." With their expensive radar and other equipment, the P2Vs were just too valuable to lose that way.  A team of Blue Sharks on anti-sub patrol off Korea. When this work got too dull Neptunes would hammer inland targets The patrol missions aren't as exciting as they used to be for the Blue Shark squadron. In fact, they're pretty dull (in World War II, American pilots flew an average of 1,800 hours of patrol for every enemy sub sighted; in this war the hours of fruitless searching are even longer). Nevertheless, in their painstaking patrols, the Neptunes may be doing noble duty by heading off submarine trouble before it starts. The squadron's leader. Commander Arthur F. Farwell, Jr. of Pensacola, Florida, knows how effective air patrols can be. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Farwell commanded a squadron whose slow flying boats were assigned the dusk-to-dawn antisubmarine watch from Cape May to Cape Hatteras on the east coast of the United States. Radar was crude in those days and Farwell's planes were not permitted to use flares because they would illuminate American shipping as well as German conning towers. So the Catalinas hunted and dived in the dark and the rate of reportable sinkings was low. Yet from May to June in 1942, the number of submarine sightings was cut down from 105 to three in the area. "We were doing a lot of good but we didn't realize it until the statistics came in," said Farwell. "Then we knew our ventures had not been in vain. I think the same may be true today. The End Charles Pomeroy In 1950 I was flying as radio/radar/ECM operator with Lt. Cdr. Wiley M. Hunt, who was our PPC and also squadron Operations officer. BE7 was a P2V-3W assigned to our crew, although Crew 7 flew as often in other aircraft as we did in our own (the same was true of other crews). I recall that four P2V-3Ws were among our 12 planes, with one leading each section of three planes: The squadron commander in BE1, the executive officer in BE3, the operations officer in BE7, and I don't recall who flew in BE10 although I'm sure it too was a 3W. Actually, the correspondent who wrote the story for Colliers flew on a mission with Crew 7, but that may have been in a P2V-3and not a 3W. Actually, there were two P2V-3s from VP-6 flying coastal interdict missions on the west coast of Korea that day (this was still Pusan perimeter time and the order of the day was to stop any movement south). Both planes were armed with sixteen 5-inch rockets and (as I recall) several 500-lb. bombs as well as the usual six 20 mm cannon in the nose, two in the tail turret, and the two 50 cal. machine guns in the upper deck turret. The PPC in the lead plane was Lt. Cdr. Wiley Hunt (the plane captain was P. R. Foster, who was lost on the shoot down by the Soviets of VP-6 plane near Vladivostok on Nov. 6, 1951) and the co-pilot was a cigar-chomping Lt. Claude. (I was in the radio position, just aft of the cockpit, and by standing and looking out between the pilots had a perfect view of the action.) Our second aircraft (BE-5, as I recall), broke off from our patrol to hit a target (a small dam, which they apparently thought would wash out the north-south road on which it faced. We had proceeded on and well south of Chinnampo came across a North Korean PC boat in a small inlet. Following the usual procedure, we climbed to around 2,000 feet and pushed over into a rocket run. We soon started taking fire (I remember clearly hearing Claude shouting at Hunt to "hit the 20s"), which also started coming from the shoreline where it seemed several other camouflaged PC boats were positioned. After breaking off from the first run, we tried to contact BE-5 on VHF, but the low altitudes at which were working in mountainous terrain made contact impossible. The Skipper called for a try on CW, but just as I was about to start we received an SOS from BE-5. They had flown into exactly the same situation and started a similar rocket attack on a target that was alert and ready. BE-5 was hit in the starboard engine, which caught on fire, and they ditched about 15 miles or so off the coast…We returned, of course, and spotted the two rafts in the water, which we marked. We also saw the PC boats headed out with the intention of capturing the downed crew. Lt. Cdr. Hunt held them at bay, flicking a rocket in their direction whenever they came too close (Hunt, by the way, was a POW in WWII, captured by the Japanese after his PBY was downed, and wanted no one to suffer a similar fate.) We were able to raise the nearest ship, the H.M.S Kenya, a British cruiser, which came on full speed. In the meantime, we were faced with a fuel problem and dumped all unnecessary weight overboard, including ammo from the upper deck and tail turrets. It was a question of whether the Kenya would arrive before we would be forced to leave the area. When the Kenya came into view (what a beautiful sight!) and we knew it would reach the rafts before the PC boats, we headed for Iwakuni. And just barely made it. A month later, the crew of BE-5 returned to Tachikawa, except for Dick Colley (AL2), who had received burns in the radar position just aft of the wing on the starboard side when the plane was hit. Dick was sent to the hospital at Yokosuka, where I later visited him (where are you, Dick? I hope you are well). Sorry, I can't recall the names of the PPC or other crew members, except for Dick Rhea, who was flying in the radio position (he was also an excellent saxaphonist)…I have tried to be as accurate as possible in recalling details of this event. Most of us believed at the time that we had flown into a flak trap. But I suppose we will never know for sure. Charles Pomeroy |